Áillohaš

Geir Tore Holm

on Nils-Aslak Valkeapää

Two excerpts from:

Encountering the Landscape Painter Nils-Aslak Valkeapää / Áillohaš

Part 2

The Sun, our father – The Earth, our mother

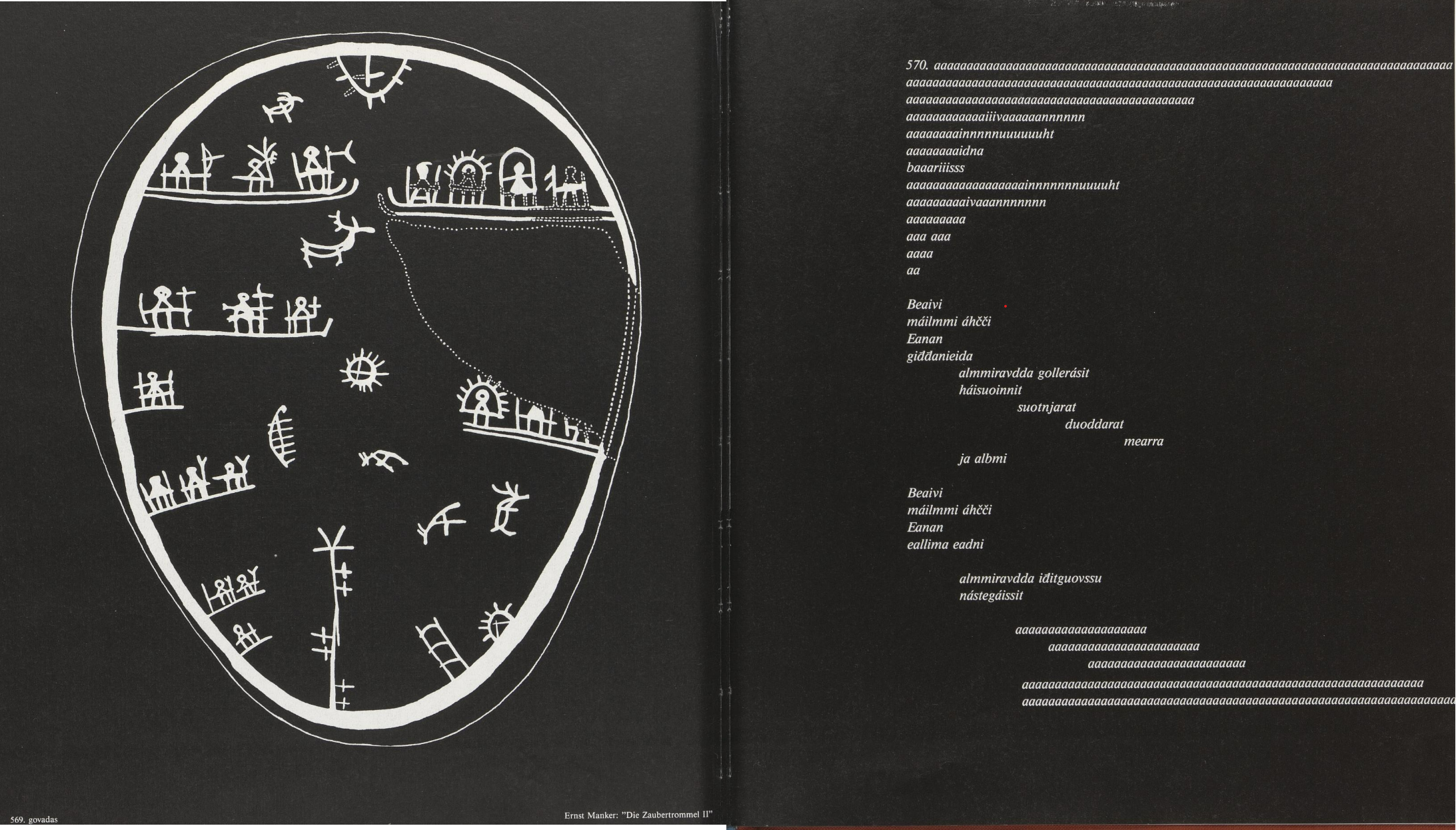

With the release of Eanni, eannázan (The Earth, My Mother) in 2001, Áillohaš ends his almost thirty-year-long artistic oeuvre with artists books. Beaivvi, áhcázan (The Sun, My Father) from 1988, is a milestone of a book and marks an awareness of a greater Sámi community. While Eanni, eannázan spreads outward into the world and the world’s reality, Beaivvi, áhcázan moves within a smaller, more intimate Sámi circle. The earlier book, with images and poems, is more akin to of a story of origins, of the lives of foremothers and fathers, and of a common Sámi landscape.

Beaivvi, áhcázan consists of a staging of archival material, alongside artistic treatments of photographs found in collections around the Nordic countries, the USA and Europe. The scope of the work is a testament to the vigorous research and the countless negotiations doubtless required for the use the material. The images are widespread in their geographical origins and cover the entirety of the Sámi region: from Peäccam and Kola Peninsula in the east, to Viesterála in the west, from Finnmárku in the north to Trööndelage and Herjedaelie in the south. There is no shortage of problematic photographs, such as the prisoner photos from Oslo after the Guovdageaidnu/Kautokeino uprising of 1852, Sámis on display in Germany and France, images of forcibly displaced Sámis in Sweden, and the typical post-card compositions that can be found at the souvenir kiosks. Even Sámi participation in polar expeditions and reindeer husbandry projects in the USA have been given a place in Beaivvi, áhcázan. The composite narrative not only shows pictures of a tough way of life – survival, Sámi life, friendship and fate – but also deals with the hurt and pain of having the photos taken in the first place. In this way, the book is emancipating contemporary art.

The reindeer are a constant theme throughout the book, directly as a form of livelihood, or as a symbol of power, and also as mythical creatures. Reindeer provide meat, milk, skins, bones, innards, and antlers, and can also be harnessed for transportation. With its alpine habitat, appearance, and movement through the landscape, the reindeer has been an icon of northern survival for thousands of years. In Beaivvi, áhcázan, Áillohaš allows the reindeer to form the poetic cycle through the use of typography. Like a stream of animals, the reindeer moves soundly through the text. We hear the reindeer and birds, but also the voices of our forefathers and mothers calling us across a timeless, mythical origin, a dream time, a drum time.

It can be stated that Beaivvi, áhcázan is a Sámi national epic, with the book’s pathos and emphasis on the past, origins, unity, pride, and heroism. The Sámi people are indeed children of the Sun, but what I find truly epic about Beaivvi, áhcázan is the radiance of the individual human being – as a part of nature. Áillohaš incorporates a circular perspective that may serve to counteract the static, the final, the original. It is an ecology, an antidote to the ethnocentrism that lurks in any widespread community project. The book ends where it begins, in physical history, in a landscape, with sieidi, birth, death, drums, stones, human being.

The composite narrative not only shows pictures of a tough way of life — survival, Sámi life, friendship and fate — but also deals with the hurt and pain of having the photos taken in the first place.

The Sámi people are indeed children of the Sun, but what I find truly epic about Beaivvi, áhcázan is the radiance of the individual human being — as a part of nature.

Credits:

Text written for the retrospective exhibition Nils-Aslak Valkeapää / Áillohaš (Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, 2020-2021). Published in the book by the same name, edited by Lars Mørch Finborud and Geir Tore Holm, (Kontur Forlag, 2020).

Pages 10-11, 24-25, 223-231, 458-461 from Beaivi, áhčážan, by Nils-Aslak Valkeapää

Published by DAT, 1988

Reproduced with permission from the Lassagammi Foundation

Material featured:

Ernst Manker - Die lappische Zaubertrommel 2, Nordiska museet

About the author

Geir Tore Holm (b.1966 in Tromsø, Norway) is a Norwegian-Sámi artist. He grew up in the Sámi community Olmmáivággi/Manndalen, Gáivuotna/Kåfjord. He lives and works at Øvre Ringstad Farm in Skiptvet, Østfold. He established Sørfinnset skole / the nord land together with Søssa Jørgensen in Gildeskål, Nordland in 2003, and was head of project in the founding of Kunstakademiet i Tromsø–UiT in 2007. Included in his artistic practice he is active as curator including projects as Sámi Art Festival (2002), River Deep, Mountain High, SDG–Sámi Center for Contemporary Art (2002), CSV–Sápmi visualized, Galleri F15 (2005), Obzidian Gaze, Riddu Riddu Festivála (2016) and Nils-Aslak Valkeapää/Áillohaš, Henie Onstad Kunstsenter (2020). He is a holder of Governments Guaranteed Income Grant and receiver of the John Savio Prize of 2015.

About the artist

Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, known as Áillohaš (b. 1943 in Enontekiö, Finland) was a Finnish-Norwegian Sámi artist, writer, and musician. Born to a family of traditional reindeer-herders, he was trained as a schoolteacher, and went on to become a pioneering artist and ambassador for Sámi culture and heritage. He received the Nordic Council Literature Prize for The Sun, My Father, in 1991, and had his international debut performing at the opening ceremony of the 1994 Winter Olympic Games in Lillehammer, Norway. He was coordinator of cultural projects in World Council of Indigenous Peoples, and a driving force in the establishing of the Sami Author’s Union. He was a key figure in the revitalisation of traditional Sámi joik, releasing 14 records in his lifetime, and winning the Prix Italia for his composition Goase dusse (English title: The Bird Symphony) in 1993. His legacy is managed by the foundation Lásságámmi.

www.lassagammi.no